EATING PROBIOTICS HELPS IMPROVE BRAIN FUNCTION

Published May 29, 2013 in Food Product Design

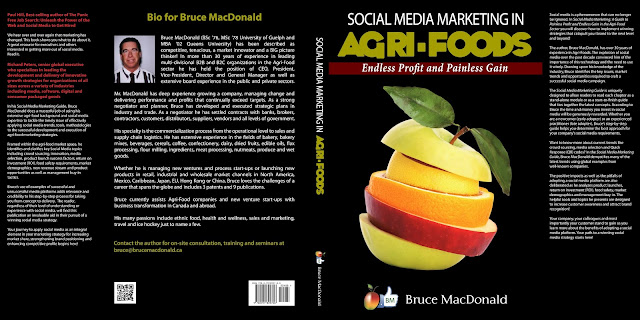

Check out my latest e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain".

LOS ANGELES—Women who regularly eat yogurt containing probiotics show altered brain function, both while in a resting state and in response to an emotion-recognition task, according to a new study published in the journal Gastroenterology. The discovery that changing the bacterial environment, or microbiota, in the gut can affect the brain carries significant implications for future research that could point the way toward dietary or drug interventions to improve brain function.

Researchers have known the brain sends signals to the gut, which is why stress and other emotions can contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms. This study, conducted by scientists with UCLA's Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer Family Center for Neurobiology of Stress and the Ahmanson-Lovelace Brain Mapping Center at UCLA, shows what has been suspected but until now had been proved only in animal studies: that signals travel the opposite way as well.

"Our findings indicate that some of the contents of yogurt may actually change the way our brain responds to the environment. When we consider the implications of this work, the old sayings 'you are what you eat' and 'gut feelings' take on new meaning," said Dr. Kirsten Tillisch, associate professor of medicine at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine and lead author. "Time and time again, we hear from patients that they never felt depressed or anxious until they started experiencing problems with their gut. Our study shows that the gut-brain connection is a two-way street."

The small study involved 36 women between the ages of 18 and 55 years. Researchers at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine divided the women into three groups: one group ate a specific yogurt containing a mix of several probiotics twice a day for four weeks; another group consumed a dairy product that looked and tasted like the yogurt but contained no probiotics; and a third group ate no product at all.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans conducted both before and after the four-week study period looked at the women's brains in a state of rest and in response to an emotion-recognition task in which they viewed a series of pictures of people with angry or frightened faces and matched them to other faces showing the same emotions. This task, designed to measure the engagement of affective and cognitive brain regions in response to a visual stimulus, was chosen because previous research in animals had linked changes in gut flora to changes in affective behaviors.

The researchers found that, compared with the women who didn't consume the probiotic yogurt, those who did showed a decrease in activity in both the insula—which processes and integrates internal body sensations, like those form the gut—and the somatosensory cortex during the emotional reactivity task.

In response to the task, the women had a decrease in the engagement of a widespread network in the brain that includes emotion-, cognition- and sensory-related areas. The women in the other two groups showed a stable or increased activity in this network.

During the resting brain scan, the women consuming probiotics showed greater connectivity between a key brainstem region known as the periaqueductal grey and cognition-associated areas of the prefrontal cortex. The women who ate no product at all, on the other hand, showed greater connectivity of the periaqueductal grey to emotion- and sensation-related regions, while the group consuming the non-probiotic dairy product showed results in between.

The researchers were surprised to find that the brain effects could be seen in many areas, including those involved in sensory processing and not merely those associated with emotion.

The knowledge that signals are sent from the intestine to the brain and that they can be modulated by a dietary change is likely to lead to an expansion of research aimed at finding new strategies to prevent or treat digestive, mental and neurological disorders, said Dr. Emeran Mayer, a professor of medicine, physiology and psychiatry at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the study's senior author.

"There are studies showing that what we eat can alter the composition and products of the gut flora—in particular, that people with high-vegetable, fiber-based diets have a different composition of their microbiota, or gut environment, than people who eat the more typical Western diet that is high in fat and carbohydrates," Mayer said. "Now we know that this has an effect not only on the metabolism but also affects brain function."

Researchers have known the brain sends signals to the gut, which is why stress and other emotions can contribute to gastrointestinal symptoms. This study, conducted by scientists with UCLA's Gail and Gerald Oppenheimer Family Center for Neurobiology of Stress and the Ahmanson-Lovelace Brain Mapping Center at UCLA, shows what has been suspected but until now had been proved only in animal studies: that signals travel the opposite way as well.

"Our findings indicate that some of the contents of yogurt may actually change the way our brain responds to the environment. When we consider the implications of this work, the old sayings 'you are what you eat' and 'gut feelings' take on new meaning," said Dr. Kirsten Tillisch, associate professor of medicine at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine and lead author. "Time and time again, we hear from patients that they never felt depressed or anxious until they started experiencing problems with their gut. Our study shows that the gut-brain connection is a two-way street."

The small study involved 36 women between the ages of 18 and 55 years. Researchers at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine divided the women into three groups: one group ate a specific yogurt containing a mix of several probiotics twice a day for four weeks; another group consumed a dairy product that looked and tasted like the yogurt but contained no probiotics; and a third group ate no product at all.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans conducted both before and after the four-week study period looked at the women's brains in a state of rest and in response to an emotion-recognition task in which they viewed a series of pictures of people with angry or frightened faces and matched them to other faces showing the same emotions. This task, designed to measure the engagement of affective and cognitive brain regions in response to a visual stimulus, was chosen because previous research in animals had linked changes in gut flora to changes in affective behaviors.

The researchers found that, compared with the women who didn't consume the probiotic yogurt, those who did showed a decrease in activity in both the insula—which processes and integrates internal body sensations, like those form the gut—and the somatosensory cortex during the emotional reactivity task.

In response to the task, the women had a decrease in the engagement of a widespread network in the brain that includes emotion-, cognition- and sensory-related areas. The women in the other two groups showed a stable or increased activity in this network.

During the resting brain scan, the women consuming probiotics showed greater connectivity between a key brainstem region known as the periaqueductal grey and cognition-associated areas of the prefrontal cortex. The women who ate no product at all, on the other hand, showed greater connectivity of the periaqueductal grey to emotion- and sensation-related regions, while the group consuming the non-probiotic dairy product showed results in between.

The researchers were surprised to find that the brain effects could be seen in many areas, including those involved in sensory processing and not merely those associated with emotion.

The knowledge that signals are sent from the intestine to the brain and that they can be modulated by a dietary change is likely to lead to an expansion of research aimed at finding new strategies to prevent or treat digestive, mental and neurological disorders, said Dr. Emeran Mayer, a professor of medicine, physiology and psychiatry at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the study's senior author.

"There are studies showing that what we eat can alter the composition and products of the gut flora—in particular, that people with high-vegetable, fiber-based diets have a different composition of their microbiota, or gut environment, than people who eat the more typical Western diet that is high in fat and carbohydrates," Mayer said. "Now we know that this has an effect not only on the metabolism but also affects brain function."

Sources:

Check out my latest e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain".

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Written by Bruce MacDonald, a 30 year veteran of the Agri-food industry, in "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain", Bruce applies his background and expertise in Agri-foods and social media to the latest trends, tools and methodologies needed to craft a successful on-line campaign. While the book focuses on the Agri-food market specifically, I believe that many of the points Bruce makes are equally applicable to most other industries.

No comments:

Post a Comment