Labour costs in spotlight as Canadian grocery wars shift to front lines

An increasingly competitive market and a wave of consolidation are forcing major grocers to look for more ways to cut costs, moves that are causing tension with employees who are feeling the squeeze.

In the latest flare-up, unionized workers at Loblaw Cos. Ltd. have set a strike deadline in Alberta and Saskatchewan. They are locked in a fight over the company’s bid to add more part-time employees and reduce wages by as much as 40 per cent, according to the union.

MORE RELATED TO THIS STORY

Metro Inc. is also moving to trim labour costs at 15 of its stores in Ontario, or even close a few of them, as the company takes a $40-million charge this year.

The initiatives come as Loblaw and Sobeys Inc. make major acquisitions, putting further pressure on rivals to change their game. Loblaw is buying Shoppers Drug Mart Corp., while Sobeys has a deal to acquire Safeway Canada.

At the same time, non-unionized U.S. discounters Wal-Mart Canada Corp. and newcomer Target Corp. are expanding and adding grocery aisles, enjoying the flexibility to shift workers’ schedules and other conditions quickly.

Canadian incumbents now are gambling that more labour agreements more favourable to companies will better arm them for the escalating battle.

“You have all these additional square foot [space] and …you have a consumer who is spending a little bit less,” Loblaw president Vicente Trius told a recent conference. “My gut feel is this is going to level off, but you will have a very competitive environment [for the next eight months].”

The United Food and Commercial Workers has taken its fight against Brampton, Ont.-based Loblaw public in an open letter to Galen G. Weston, the retailer’s executive chairman and company pitchman. In full-page advertisements last week, the UFCW pleaded with him to “do the right thing” and stop trying to slash employees’ work hours and roll back their wages by 30 per cent to 40 per cent.

“We can’t make a living and we certainly cannot ‘exceed customer expectations,’” the letter said. “Stores are a mess and food safety is an issue.”

Loblaw spokeswoman Julija Hunter said in an e-mail on Monday that the company is in labour negotiations and can’t address specific questions. “But I do want to state that our customers are at the heart of every decision we make, and we would not compromise that priority in the way we conduct our business.”

She said Loblaw has a responsibility to ensure the contract it negotiates allows it to remain competitive “now and in the future.”

Members of three Loblaw unions had voted to strike by Oct. 6, but the local in Manitoba reached a tentative agreement last Thursday. Two others – in Alberta and Saskatchewan – representing more than 12,000 employees in 82 outlets, including Real Canadian Superstores and Extra Foods, remain locked in talks.

For years, grocers have been trying to gain the flexibility to change employees’ hours and other conditions while converting stores to lower-cost banners, such as Loblaw’s No Frills, where union agreements allow for lower wages and benefits.

Montreal-based Metro wants to lower wages and reduce benefits at 15 Ontario stores, starting with a Richmond Hill outlet it plans to convert to the discount Food Basics banner. Four other stores – in Bracebridge, Huntsville, Tillsonburg and Sault Ste. Marie – will adopt lower-compensation contracts, and more moves will come by next spring, spokeswoman Marie-Claude Bacon said.

“The benefits will be a higher top line, a better bottom line …for these stores that are converted,” Metro chief executive Eric La Fleche said during a recent conference call.

Grocers are grappling with consolidation, as well as essentially zero inflation this year, forcing them to try to reduce labour and other expenses, said Sylvain Charlebois, a food policy professor at the University of Guelph in Ontario. “Margins are very tight,” he said. “They have to really rethink their business model.”

But Kendra Coulter, a labour studies professor at Ontario’s Brock University, said grocers risk unstocked shelves and poor customer service if they don’t ensure financial stability for their employees. The shift to part-timers takes a toll, she noted: Although they make up 19 per cent of the total labour force, the rate is as high as 65 per cent among cashiers in grocery and department stores, up from 58 per cent in 1998, her data show. “There are benefits to reducing turnover.”

Tom Hesse, chief negotiator for UFCW Local 401 in Alberta, said Loblaw was forced to temporarily close a superstore in Calgary several years ago because of serious mouse infestations. He said publicity about such problems lead to fewer customers, less business and job cuts, which make it difficult for workers to keep up.

He said Loblaw wants to cut wages of cashiers and shelf-stockers to between $11.65 to $14.65 an hour, from $11.65 to $24.24 an hour currently. The company wants to cap part-time workers’ pay at $14.65 an hour, and full-timers wages at $16.45, he said. The union is asking for 4 per cent to 8 per cent annual wage increases and limits on self-scanners, suppliers stocking shelves’ and hiring of new staff.

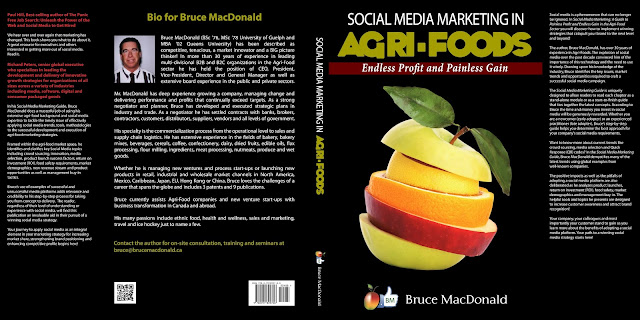

Check out my latest e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain"

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Thanks for taking the time

No comments:

Post a Comment