Brazil’s disappointing economy

Stuck in the mud

Published June 8, 2013 in The Economist

Feeble growth has forced a change of course. But the government’s room for manoeuvre is more limited than it was

FAILING to meet low expectations is becoming a habit for Brazil’s economy. Figures published on May 29th showed that in the first quarter of this year it grew by just 0.6% (2.4% annualised), well short of the recovery analysts had expected. For the first time in years the country is running a trade deficit. Its primary fiscal surplus (ie, before interest payments) is shrinking and government debt is growing. Other emerging economies are also cutting growth forecasts, as China slows and the euro zone slumps. But Brazil’s woes started earlier than most and seem to be home-grown. Inflation close to 6.5% despite low growth suggests domestic rigidities are the main problem, rather than weak foreign demand.

After becoming president in 2011, Dilma Rousseff sought to stimulate growth by hiking public spending and the minimum wage, and forcing state-run banks to lend more. The resulting inflation was tackled not by raising interest rates but by cutting sales taxes and holding down the price of items with a big impact on the inflation index, including food, petrol and bus fares. Until recently voters reacted favourably, though the economy did not. Polls in March gave Ms Rousseff a record-breaking 79% approval rating, making her the clear favourite to win next year’s presidential election and allowing her to put off economic adjustments until a second term.

But stagnant growth is now hitting Brazilians in their pockets. After successive wage rises, this year’s pay deals barely outpace inflation. Already indebted, households are reining in their spending. Consumer confidence is falling and more people say rising prices are their biggest economic worry.

The swift deterioration in the economic data and public sentiment seems to have forced the government’s hand. Despite the weak growth figures, the Central Bank surprised markets by raising the base interest rate from 7.5% to 8%, making Brazil the only big economy currently tightening monetary policy. The bank’s governor, Alexandre Tombini, said the move had Ms Rousseff’s “full support”. It went some way to restoring the institution’s inflation-fighting credentials, badly dented by the president’s determination to push down rates even as inflation rose.

The bank will have to raise rates again to bring inflation nearer its 4.5% target. On June 4th the government scrapped a tax on foreign purchases of bonds, in order to encourage currency inflows and slow the weakening of the real, which has fuelled inflation by making imports pricier. The finance ministry will be scrutinised for signs of a return to rectitude, after using creative accounting to hit its primary-surplus target last year. The departure of Nelson Barbosa, a senior official who reportedly opposed the fiscal fiddles, worries many analysts.

Most keenly awaited is evidence that the government is serious about its promise to stop trying to boost consumption and instead encourage investment, currently just 18.4% of GDP. During the first quarter investment picked up, but mostly because of a recovery in sales of heavy-goods vehicles, which were depressed last year by stricter rules on emissions.

Ms Rousseff has exhorted businesses to invest more. But the government’s own actions are one reason they have failed to heed her call. Holding down petrol prices to slow the rise in inflation weakened the balance-sheet of Petrobras, the state-controlled oil giant, and played havoc with the sugarcane-ethanol industry, which competes directly with petrol at the pump. A delay in introducing new mining laws and a row about how to share oil royalties have put exploration and development on hold in both industries.

In August the government said that early in 2013 it would start to auction road and railway concessions to the private sector. But its unwillingness to allow a competitive return put investors off, and the auctions were delayed. Clumsy interventions in the electricity and banking industries completed the picture of a heavy-handed, anti-business administration.

Pork and persuasion

Engineering an investment boom will mean breaking at least some of these logjams. A successful drilling-rights auction last month and plans to sell a vast new field off the coast of Rio de Janeiro in October have raised hopes that investment in the oil industry will soon pick up. And in recent weeks the government has accepted that it must offer juicier returns to lure bidders to its road and rail concessions. A string of successful sales would go a long way to boosting business confidence and private-sector investment—and to providing the upgrades Brazil’s outdated infrastructure needs if growth is to pick up.

But just as the room for economic manoeuvre is diminishing, the political landscape is becoming harder to navigate. Though the governing coalition controls 80% of Congress, its members include everyone from communists to evangelical Christians, and many unprincipled power-seekers. A former bureaucrat with no previous experience of elected office, Ms Rousseff has proved ill-suited to the shuttle diplomacy required to coax her so-called allies into backing her plans. Brusque and impatient, she rarely talks to congressmen. They regard the proxies she sends as arrogant and sometimes incompetent.

Last month a truculent Congress nearly blocked a much-needed new law that will increase competition and private investment in the country’s crowded, outdated ports. Passing the bill took all-night sessions in the lower house, arm-twisting in the Senate, and the promise of a billion reais ($500m) in pork-barrel spending. The Party of the Brazilian Democratic Movement, Ms Rousseff’s largest coalition partner, is now threatening to support the party of Eduardo Campos, a likely presidential challenger, in some state races next year and to field its own candidates in others. This is probably just a bargaining ploy. But it suggests that Ms Rousseff will have to pay a high price for getting her infrastructure plans off the drawing board.

FAILING to meet low expectations is becoming a habit for Brazil’s economy. Figures published on May 29th showed that in the first quarter of this year it grew by just 0.6% (2.4% annualised), well short of the recovery analysts had expected. For the first time in years the country is running a trade deficit. Its primary fiscal surplus (ie, before interest payments) is shrinking and government debt is growing. Other emerging economies are also cutting growth forecasts, as China slows and the euro zone slumps. But Brazil’s woes started earlier than most and seem to be home-grown. Inflation close to 6.5% despite low growth suggests domestic rigidities are the main problem, rather than weak foreign demand.

After becoming president in 2011, Dilma Rousseff sought to stimulate growth by hiking public spending and the minimum wage, and forcing state-run banks to lend more. The resulting inflation was tackled not by raising interest rates but by cutting sales taxes and holding down the price of items with a big impact on the inflation index, including food, petrol and bus fares. Until recently voters reacted favourably, though the economy did not. Polls in March gave Ms Rousseff a record-breaking 79% approval rating, making her the clear favourite to win next year’s presidential election and allowing her to put off economic adjustments until a second term.

But stagnant growth is now hitting Brazilians in their pockets. After successive wage rises, this year’s pay deals barely outpace inflation. Already indebted, households are reining in their spending. Consumer confidence is falling and more people say rising prices are their biggest economic worry.

The swift deterioration in the economic data and public sentiment seems to have forced the government’s hand. Despite the weak growth figures, the Central Bank surprised markets by raising the base interest rate from 7.5% to 8%, making Brazil the only big economy currently tightening monetary policy. The bank’s governor, Alexandre Tombini, said the move had Ms Rousseff’s “full support”. It went some way to restoring the institution’s inflation-fighting credentials, badly dented by the president’s determination to push down rates even as inflation rose.

The bank will have to raise rates again to bring inflation nearer its 4.5% target. On June 4th the government scrapped a tax on foreign purchases of bonds, in order to encourage currency inflows and slow the weakening of the real, which has fuelled inflation by making imports pricier. The finance ministry will be scrutinised for signs of a return to rectitude, after using creative accounting to hit its primary-surplus target last year. The departure of Nelson Barbosa, a senior official who reportedly opposed the fiscal fiddles, worries many analysts.

Most keenly awaited is evidence that the government is serious about its promise to stop trying to boost consumption and instead encourage investment, currently just 18.4% of GDP. During the first quarter investment picked up, but mostly because of a recovery in sales of heavy-goods vehicles, which were depressed last year by stricter rules on emissions.

Ms Rousseff has exhorted businesses to invest more. But the government’s own actions are one reason they have failed to heed her call. Holding down petrol prices to slow the rise in inflation weakened the balance-sheet of Petrobras, the state-controlled oil giant, and played havoc with the sugarcane-ethanol industry, which competes directly with petrol at the pump. A delay in introducing new mining laws and a row about how to share oil royalties have put exploration and development on hold in both industries.

In August the government said that early in 2013 it would start to auction road and railway concessions to the private sector. But its unwillingness to allow a competitive return put investors off, and the auctions were delayed. Clumsy interventions in the electricity and banking industries completed the picture of a heavy-handed, anti-business administration.

Pork and persuasion

Engineering an investment boom will mean breaking at least some of these logjams. A successful drilling-rights auction last month and plans to sell a vast new field off the coast of Rio de Janeiro in October have raised hopes that investment in the oil industry will soon pick up. And in recent weeks the government has accepted that it must offer juicier returns to lure bidders to its road and rail concessions. A string of successful sales would go a long way to boosting business confidence and private-sector investment—and to providing the upgrades Brazil’s outdated infrastructure needs if growth is to pick up.

But just as the room for economic manoeuvre is diminishing, the political landscape is becoming harder to navigate. Though the governing coalition controls 80% of Congress, its members include everyone from communists to evangelical Christians, and many unprincipled power-seekers. A former bureaucrat with no previous experience of elected office, Ms Rousseff has proved ill-suited to the shuttle diplomacy required to coax her so-called allies into backing her plans. Brusque and impatient, she rarely talks to congressmen. They regard the proxies she sends as arrogant and sometimes incompetent.

Last month a truculent Congress nearly blocked a much-needed new law that will increase competition and private investment in the country’s crowded, outdated ports. Passing the bill took all-night sessions in the lower house, arm-twisting in the Senate, and the promise of a billion reais ($500m) in pork-barrel spending. The Party of the Brazilian Democratic Movement, Ms Rousseff’s largest coalition partner, is now threatening to support the party of Eduardo Campos, a likely presidential challenger, in some state races next year and to field its own candidates in others. This is probably just a bargaining ploy. But it suggests that Ms Rousseff will have to pay a high price for getting her infrastructure plans off the drawing board.

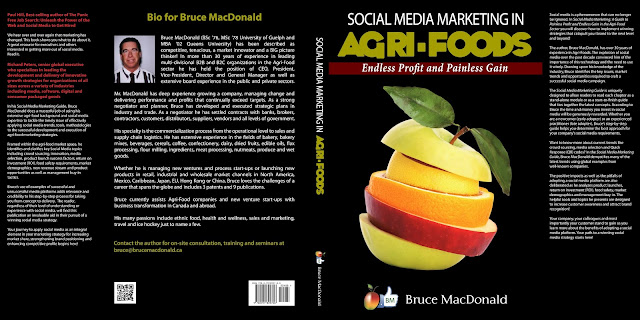

Check out my latest e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain".

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Written by Bruce MacDonald, a 30 year veteran of the Agri-food industry, in "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain", Bruce applies his background and expertise in Agri-foods and social media to the latest trends, tools and methodologies needed to craft a successful on-line campaign. While the book focuses on the Agri-food market specifically, I believe that many of the points Bruce makes are equally applicable to most other industries.

No comments:

Post a Comment