LAWYERS DIVIDED ON STRENGTH OF RED BULL LAWSUIT

Posted in News, Energy Drinks, Beverages, Ready-To-Drink (RTD) Beverages, Caffeine, Regulatory,Lawsuit, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Labeling, Heart Health, Cardiovascular, Dietary Supplements, Retail, Health Claims, BI Nutraceuticals, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition (CFSAN)

BROOKLYN, N.Y.—Lawyers are divided on the strength of a wrongful death lawsuit that was filed in October against Red Bull in the case of a 33-year-old man who fell into cardiac arrest after consuming an energy drink while playing basketball.

"There are a thousand reasons" why someone can die, Georgia-based personal injury attorney Chris Simon said in a phone interview. "In almost all state courts, there is a pretty high bar for medical proof. You have to rule out a myriad number of factors, lifestyle and genetics."

In a wrongful death case filed last year against Monster Beverage Corp., the company blamed the death of 14-year-old Anais Fournier on a preexisting medical condition. The case is pending in California Superior Court in Riverside County and the parties must complete mediation by March 10, 2014.

Whether New Yorker Cory Terry suffered from a preexisting medical condition that would predispose him to a heart attack is unknown. His grandmother Patricia Terry told the New York Daily News that her grandson was healthy and regularly drank Red Bull. As Cory Terry's grandmother and administrator of his estate, Patricia Terry is the named plaintiff.

Ilya Novofastovsky, a New York attorney who filed the lawsuit against the energy-drink company, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The New York Daily News said the cause of death was idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.

"Dilated cardiomyopathy occurs when your heart's main pumping chamber (the left ventricle) doesn't pump as efficiently as a healthy heart," the Mayo Clinic explains. According to the medical research group, several conditions can cause dilated cardiomyopathy, including birth defects, drug and alcohol abuse, genetics, infections, cancer medications and exposures to metals and toxic compounds.

It appears the coroner didn't know what caused Terry's condition because the Mayo Clinic explains that "cases are called idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy" when the cause cannot be determined.

Paul Rheingold, a New York-based plaintiff's attorney who has been practicing law since 1958, isn't convinced the Red Bull case is a loser even if Terry suffered from a preexisting medical condition. If Terry was aware of a preexisting medical condition, his lawyers could argue that had there been an appropriate warning on Red Bull's label, he would not have consumed the drink, Rheingold explained in a phone interview.

The lawsuit already makes a similar contention. Terry never would have drank Red Bull had he known about the risks of suffering a heart attack due to consuming an energy drink that contains "exorbitant levels of caffeine, taurine and other harmful chemicals", Novofastovsky wrote in the lawsuit.

Rheingold also pointed out the plaintiff doesn't have to establish that Red Bull was the only cause of Terry's death.

"All Red Bull has to be is a substantial factor under New York law," Rheingold said. "It doesn't have to be a full cause".

Several years ago, Rheingold was involved with multi-district product liability litigation against companies selling dietary supplements that contained the herb ephedra. He said experts testified that ephedra and caffeine increased heart rate or blood pressure. All the cases settled in the Southern District of New York before federal Judge Jed Rakoff, he said.

The 21-page lawsuit against Red Bull contains few facts about Terry. According to the complaint, on Nov. 8, 2011, the New Yorker—and father of a 13-year-old boy—drank Red Bull before and while playing basketball at the Stephen Decatur School in Brooklyn. Terry subsequently fell into cardiac arrest. He received advance life support at the scene and was taken to the Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center in Brooklyn where he was pronounced dead.

Red Bull declined to comment on the case. However, a spokesperson noted the energy drink "is available in more than 165 countries because health authorities across the world have concluded that Red Bull Energy Drink is safe to consume."

"An 8.4-ounce can of Red Bull Energy Drink contains 80mg of caffeine, about the equivalent amount of caffeine as a cup of home-brewed coffee," the spokesperson said.

The lawsuit cited a number of deaths linked to Red Bull in Canada and Europe as well as research literature that has associated caffeine-laden energy drinks with medical problems. For instance, in 2000, Limerick University student Ross Rooney died during a basketball game after drinking Red Bull, and a Dublin jury questioned Red Bull's role in his death, according to the complaint.

Reports submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) potentially linked Red Bull to 21 adverse events from the years Jan. 1, 2004 through Oct. 23, 2012. The reports received by FDA's Center for Food Safety Adverse Event Reporting System cite such symptoms as anxiety, blindness, chest pain, fatigue and vomiting. None of the 21 adverse events list death as the "outcome", although a few cite "life-threatening".

Red Bull is marketed as a conventional food rather than a dietary supplement, according to the FDA document. The distinction is important because dietary supplement companies are required to submit to FDA serious adverse event reports (AERs) like death and a life-threatening experience while conventional foods like Red Bull are not subject to such a requirement. The adverse events associated with Red Bull may have originated from consumers and healthcare practitioners rather than the company itself.

FDA has emphasized that such adverse reports do not reflect its conclusion that the products caused the medical problems. And the 21 events represent a miniscule fraction of Red Bull's total sales. In 2012 alone, the company sold 5.2 billion cans, with substantial sales growth in South Africa (52%), Japan (51%), Saudi Arabia (38%), France (21%), the United States (17%) and Germany (14%).

Novofastovsky filed the lawsuit before the Kings County Supreme Court. Red Bull North America, Inc., cannot get the case into federal court based on the legal doctrine known as "diversity jurisdiction" because Red Bull was incorporated in New York and Terry is from the same state.

"If I was the defendant, I'd rather be in federal court on a case like this because it's much more demanding—what the plaintiff has to prove," Rheingold said.

It's possible Red Bull will move to transfer the case to U.S. District Court based on the argument that the lawsuit involves a question of federal law. But the complaint only asserts state causes of action, including strict liability-design defect, strict liability-failure to warn, negligence-design, manufacturer and sale, negligence-failure to warn, fraud, breach of implied warranties and wrongful death.

Litigator Maxwell Kennerly of the Philadelphia-based Beasley Firm LLC argued Red Bull may have a problem defending Novofastovsky's claim alleging failure to warn. He cited New York law, which requires manufacturers to "warn against latent dangers resulting from foreseeable uses of its product of which it knew or should have known." According to Kennerly, Red Bull's can and box contain no warnings, while its website asserts that health authorities around the world have concluded the drink is safe to consume.

Whether a warning would have prevented Terry from drinking Red Bull while shooting hoops is a question a jury will have to decide, he wrote.

That's if the dispute makes it to a jury after what could be years of discovery, motions and expert battles.

Rheingold said it takes a number of years to get to trial in New York state court, "and the more complicated the case, the longer it is." Arlene Hackel with the New York State Unified Court System could not provide data on the average time that it takes to get a case to trial.

As was widely reported at the time the Red Bull lawsuit was filed, Terry's lawyer is seeking $85 million. A New York rule actually forbids a complaint from stating the amount of damages to which a plaintiff deems himself entitled.

On blogs online, some attorneys pointed out that the Red Bull complaint violates this rule. The statute, however, does not provide a penalty for violating CPLR Section 3017c, Evan Goldberg, a New York attorney with Trolman, Glaser & Lichtman, P.C., said in an emailed statement.

"A motion could be brought to dismiss the complaint or strike part of it, but since there is no legal significance to the amount, it's unlikely to have any effect on the litigation," added Goldberg, past chair of the New York State Bar Association Trial Lawyers Section.

Still, some lawyers including New York's Eric Turkewitz ranted online about the issue, contending that salacious headlines like the one in the Post article poison the potential jury pool. The personal injury and medical malpractice lawyer argued Terry's attorney Novafastovsky was either ignorant about the rule or was hungry for news headlines.

"Every time I pick a jury I am forced to deal with unusual claims that appear in press headlines, distracting me from the job I was hired to do," he wrote in his blog. "The biases are there, planted firmly in their brains by lawyers that make monster claims that bury the reason they actually took on the suit."

The Terry case bears some resemblance to a 2010 lawsuit that was filed against the distributor of 5-hour Energy shots, Living Essentials, on behalf of a 27-year-old man who suffered a heart attack and died. According to the complaint, Antonio James Hassell suffered an arrhythmia while playing basketball at a high school with his friends. The lawsuit blamed 5-hour Energy for the cause of death, citing Hassell's treating physician.

In 2011, the case against Living Essentials, Bio Clinical Development, Inc. and Manoj Bhargava was voluntarily dismissed at the plaintiff's request. Living Essentials and an attorney for the plaintiff, David Randolph Smith, did not respond to a request for comment.

Records reviewed last year by The New York Times revealed reports of 13 deaths linked to 5-hour Energy and more than 30 filings that involved serious or life-threatening injuries. In a statement to theTimes, Living Essentials said it considered "reports of any potential adverse event tied to our products very seriously."

As one would expect, energy-drink companies have denied that their products caused any deaths. For instance, Monster Beverage declared in a Nov. 12 regulatory filing that the Fournier case "is without merit" and the company "plans a vigorous defense". Even if damages were awarded in the suit, Monster said it "would not have a material adverse effect" on its financial position.

But the rising number of wrongful death lawsuits—and the ghastly publicity and increased regulatory scrutiny that follows them—could gradually sap the growth of the energy-drink market.

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Thanks for taking the time

"There are a thousand reasons" why someone can die, Georgia-based personal injury attorney Chris Simon said in a phone interview. "In almost all state courts, there is a pretty high bar for medical proof. You have to rule out a myriad number of factors, lifestyle and genetics."

In a wrongful death case filed last year against Monster Beverage Corp., the company blamed the death of 14-year-old Anais Fournier on a preexisting medical condition. The case is pending in California Superior Court in Riverside County and the parties must complete mediation by March 10, 2014.

Whether New Yorker Cory Terry suffered from a preexisting medical condition that would predispose him to a heart attack is unknown. His grandmother Patricia Terry told the New York Daily News that her grandson was healthy and regularly drank Red Bull. As Cory Terry's grandmother and administrator of his estate, Patricia Terry is the named plaintiff.

Ilya Novofastovsky, a New York attorney who filed the lawsuit against the energy-drink company, did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

The New York Daily News said the cause of death was idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy.

"Dilated cardiomyopathy occurs when your heart's main pumping chamber (the left ventricle) doesn't pump as efficiently as a healthy heart," the Mayo Clinic explains. According to the medical research group, several conditions can cause dilated cardiomyopathy, including birth defects, drug and alcohol abuse, genetics, infections, cancer medications and exposures to metals and toxic compounds.

It appears the coroner didn't know what caused Terry's condition because the Mayo Clinic explains that "cases are called idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy" when the cause cannot be determined.

Paul Rheingold, a New York-based plaintiff's attorney who has been practicing law since 1958, isn't convinced the Red Bull case is a loser even if Terry suffered from a preexisting medical condition. If Terry was aware of a preexisting medical condition, his lawyers could argue that had there been an appropriate warning on Red Bull's label, he would not have consumed the drink, Rheingold explained in a phone interview.

The lawsuit already makes a similar contention. Terry never would have drank Red Bull had he known about the risks of suffering a heart attack due to consuming an energy drink that contains "exorbitant levels of caffeine, taurine and other harmful chemicals", Novofastovsky wrote in the lawsuit.

Rheingold also pointed out the plaintiff doesn't have to establish that Red Bull was the only cause of Terry's death.

"All Red Bull has to be is a substantial factor under New York law," Rheingold said. "It doesn't have to be a full cause".

Several years ago, Rheingold was involved with multi-district product liability litigation against companies selling dietary supplements that contained the herb ephedra. He said experts testified that ephedra and caffeine increased heart rate or blood pressure. All the cases settled in the Southern District of New York before federal Judge Jed Rakoff, he said.

The 21-page lawsuit against Red Bull contains few facts about Terry. According to the complaint, on Nov. 8, 2011, the New Yorker—and father of a 13-year-old boy—drank Red Bull before and while playing basketball at the Stephen Decatur School in Brooklyn. Terry subsequently fell into cardiac arrest. He received advance life support at the scene and was taken to the Woodhull Medical and Mental Health Center in Brooklyn where he was pronounced dead.

Red Bull declined to comment on the case. However, a spokesperson noted the energy drink "is available in more than 165 countries because health authorities across the world have concluded that Red Bull Energy Drink is safe to consume."

"An 8.4-ounce can of Red Bull Energy Drink contains 80mg of caffeine, about the equivalent amount of caffeine as a cup of home-brewed coffee," the spokesperson said.

The lawsuit cited a number of deaths linked to Red Bull in Canada and Europe as well as research literature that has associated caffeine-laden energy drinks with medical problems. For instance, in 2000, Limerick University student Ross Rooney died during a basketball game after drinking Red Bull, and a Dublin jury questioned Red Bull's role in his death, according to the complaint.

Reports submitted to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) potentially linked Red Bull to 21 adverse events from the years Jan. 1, 2004 through Oct. 23, 2012. The reports received by FDA's Center for Food Safety Adverse Event Reporting System cite such symptoms as anxiety, blindness, chest pain, fatigue and vomiting. None of the 21 adverse events list death as the "outcome", although a few cite "life-threatening".

Red Bull is marketed as a conventional food rather than a dietary supplement, according to the FDA document. The distinction is important because dietary supplement companies are required to submit to FDA serious adverse event reports (AERs) like death and a life-threatening experience while conventional foods like Red Bull are not subject to such a requirement. The adverse events associated with Red Bull may have originated from consumers and healthcare practitioners rather than the company itself.

FDA has emphasized that such adverse reports do not reflect its conclusion that the products caused the medical problems. And the 21 events represent a miniscule fraction of Red Bull's total sales. In 2012 alone, the company sold 5.2 billion cans, with substantial sales growth in South Africa (52%), Japan (51%), Saudi Arabia (38%), France (21%), the United States (17%) and Germany (14%).

Novofastovsky filed the lawsuit before the Kings County Supreme Court. Red Bull North America, Inc., cannot get the case into federal court based on the legal doctrine known as "diversity jurisdiction" because Red Bull was incorporated in New York and Terry is from the same state.

"If I was the defendant, I'd rather be in federal court on a case like this because it's much more demanding—what the plaintiff has to prove," Rheingold said.

It's possible Red Bull will move to transfer the case to U.S. District Court based on the argument that the lawsuit involves a question of federal law. But the complaint only asserts state causes of action, including strict liability-design defect, strict liability-failure to warn, negligence-design, manufacturer and sale, negligence-failure to warn, fraud, breach of implied warranties and wrongful death.

Litigator Maxwell Kennerly of the Philadelphia-based Beasley Firm LLC argued Red Bull may have a problem defending Novofastovsky's claim alleging failure to warn. He cited New York law, which requires manufacturers to "warn against latent dangers resulting from foreseeable uses of its product of which it knew or should have known." According to Kennerly, Red Bull's can and box contain no warnings, while its website asserts that health authorities around the world have concluded the drink is safe to consume.

Whether a warning would have prevented Terry from drinking Red Bull while shooting hoops is a question a jury will have to decide, he wrote.

That's if the dispute makes it to a jury after what could be years of discovery, motions and expert battles.

Rheingold said it takes a number of years to get to trial in New York state court, "and the more complicated the case, the longer it is." Arlene Hackel with the New York State Unified Court System could not provide data on the average time that it takes to get a case to trial.

As was widely reported at the time the Red Bull lawsuit was filed, Terry's lawyer is seeking $85 million. A New York rule actually forbids a complaint from stating the amount of damages to which a plaintiff deems himself entitled.

On blogs online, some attorneys pointed out that the Red Bull complaint violates this rule. The statute, however, does not provide a penalty for violating CPLR Section 3017c, Evan Goldberg, a New York attorney with Trolman, Glaser & Lichtman, P.C., said in an emailed statement.

"A motion could be brought to dismiss the complaint or strike part of it, but since there is no legal significance to the amount, it's unlikely to have any effect on the litigation," added Goldberg, past chair of the New York State Bar Association Trial Lawyers Section.

Still, some lawyers including New York's Eric Turkewitz ranted online about the issue, contending that salacious headlines like the one in the Post article poison the potential jury pool. The personal injury and medical malpractice lawyer argued Terry's attorney Novafastovsky was either ignorant about the rule or was hungry for news headlines.

"Every time I pick a jury I am forced to deal with unusual claims that appear in press headlines, distracting me from the job I was hired to do," he wrote in his blog. "The biases are there, planted firmly in their brains by lawyers that make monster claims that bury the reason they actually took on the suit."

The Terry case bears some resemblance to a 2010 lawsuit that was filed against the distributor of 5-hour Energy shots, Living Essentials, on behalf of a 27-year-old man who suffered a heart attack and died. According to the complaint, Antonio James Hassell suffered an arrhythmia while playing basketball at a high school with his friends. The lawsuit blamed 5-hour Energy for the cause of death, citing Hassell's treating physician.

In 2011, the case against Living Essentials, Bio Clinical Development, Inc. and Manoj Bhargava was voluntarily dismissed at the plaintiff's request. Living Essentials and an attorney for the plaintiff, David Randolph Smith, did not respond to a request for comment.

Records reviewed last year by The New York Times revealed reports of 13 deaths linked to 5-hour Energy and more than 30 filings that involved serious or life-threatening injuries. In a statement to theTimes, Living Essentials said it considered "reports of any potential adverse event tied to our products very seriously."

As one would expect, energy-drink companies have denied that their products caused any deaths. For instance, Monster Beverage declared in a Nov. 12 regulatory filing that the Fournier case "is without merit" and the company "plans a vigorous defense". Even if damages were awarded in the suit, Monster said it "would not have a material adverse effect" on its financial position.

But the rising number of wrongful death lawsuits—and the ghastly publicity and increased regulatory scrutiny that follows them—could gradually sap the growth of the energy-drink market.

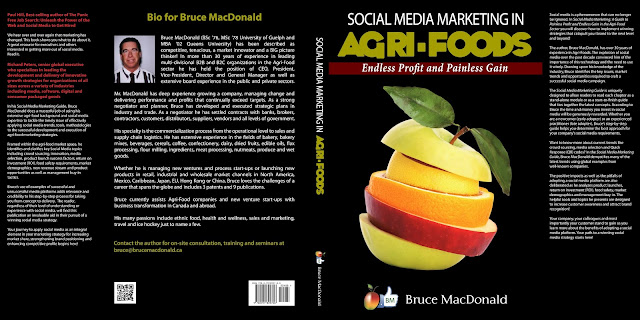

Check out my new e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain"

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Thanks for taking the time

No comments:

Post a Comment