Illustration by Tim Lahan

We’re Not Powerless Against Oreos

When Connecticut College researchers announced a few weeks ago that they found Oreo cookies to be as addictive as cocaine -- in rats -- they made headlines.

Their study (actually, their abstract; the study hasn’t yet been published) quickly drew well-founded criticism for its weak methodology and overstated conclusions. Nonetheless, the underlying premise -- that habitual excessive eating leads to the kind of brain changes that are seen in drug addiction -- is worth a closer look because it is a staple of anti-obesity campaigns and may someday be used in lawsuits against Big Food.

Too often, this argument assumes that brain changes associated with addiction are all-powerful.

First, the experiment: The researchers allowed rats access to two side-by-side chambers, one in which they could eat tasty Oreos and one where they could nibble bland rice cakes. Once the rats learned which chamber had which food, the researchers cut off the supply and allowed the animals to wander into the empty rooms. As expected, the rats favored the chamber that had contained Oreos.

The researchers then ran a variation of the experiment with a different set of rats, this time giving them an injection of cocaine in one chamber and an injection of saline in the other. When allowed to roam, the rats preferred to linger in the cocaine chamber, spending about as much time there as the first group spent in the Oreo room.

Limited Options

What does the study tell us? Not a lot. To begin, it doesn’t show that rats were as attracted to Oreos as they were to cocaine. How could it? There was no head-to-head comparison. The options were cookies or rice cakes and cocaine or saline.

Then the researchers euthanized the rats and examined their brains. Compared with the drug-injected rats, the Oreo eaters’ brains displayed a greater activation of neurons in the nucleus accumbens, a key area of reward circuitry. The saline recipients and rice-cake eaters lagged far behind in neuronal activation.

So, rats like Oreos. Possibly, they like them more than they like cocaine. I say possibly because the different activation patterns in the nucleus accumbens could reflect the fact that the rats actively approached and ingested cookies, while their counterparts had drugs administered to them. In any case, enhanced neuronal activation per se does not indicate addiction; it suggests only that the creature anticipated or experienced pleasure.

Why an Oreo study in the first place? “We chose Oreos,” explained Jamie Honohan, the neuroscience student at Connecticut College who initiated the study, because “products containing high amounts of fat and sugar are heavily marketed in communities with lower socioeconomic statuses.” In light of the findings, the team reported that “high fat/sugar foods and drugs of abuse trigger brain addictive processes to the same degree and lend support to the hypothesis that maladaptive eating behaviors contributing to obesity can be compared to drug addiction.”

Over the past decade, the hypothesis that fast food and junk food can be as enslaving as cocaine has gained currency, and it ostensibly is supported by a flood of studies documenting neural changes in rats fed tasty foods full of sugar and fat. The argument dovetails nicely with the “brain disease” model of addiction popularized by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the American Society of Addiction Medicine. The general idea is that once someone is addicted, “you can’t just tell the addict ‘Stop’ any more than you can tell the smoker ‘Don’t have emphysema,’” says Alan Leshner, former head of the NIDA.

In other words, “food addiction” prompts unstoppable harmful behavior. But this is just not true. Both humans (and rodents) can still be influenced by alternatives.

Avoiding Boredom

Rats that find themselves alone in a cage with nothing better to do have been known to drink a morphine solution or press a lever that delivers cocaine through an implanted intravenous line until they die. But when their cage contains “alternative reinforcers” such as sweet water to drink, other rats to play with or an abundance of toys, then -- brain changes notwithstanding -- they drink morphine or press the lever much less.

For humans, alternative reinforcers can mean the difference between addiction and sobriety. Enlightened rehab programs use rewards, such as vouchers for gifts cards or movie tickets, to encourage job training and attendance at treatment or Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous meetings.

When there are no attractive choices, people will continue to choose drugs. Granted, when it comes to addiction, the word “choose” is fraught; no one chooses to be an addict or, for that matter, to be overweight. But they do choose momentary gratification or relief -- which is rational in the short term, however self-destructive it is in the long run.

In other words, reason plays a role; uncontrollable brain circuits don’t just take over.

Yes, cravings can be powerful enough to undermine the most heartfelt resolutions. But that’s why it’s imperative for people with excessive habits to place obstacles between themselves and the things they crave. For drug addicts, relapse-prevention tactics include avoiding people, places or things associated with drug use and directly depositing paychecks or tearing up automated teller machine cards to avoid carrying ready cash. Developing alternative modes of gratification and avoiding boredom (a common source of vulnerability) can help control both drug addiction and overeating.

The plaintiffs’ bar has been paying attention to the concept of food addiction. Previous class-action suits against McDonald’s Corp., Burger King Worldwide Inc. and other fast-food companies have alleged consumer fraud for failing to conspicuously disclose the ingredients and effects of their food, much of which is high in fat, salt, sugar and cholesterol. So far, none of these lawsuits has succeeded, but brain studies give lawyers a new tack. The trouble is, there’s no scientific justification for using food-addiction studies to put Big Oreo in the crosshairs. Neither drug addicts nor overeaters are biologically fated to pursue their habits.

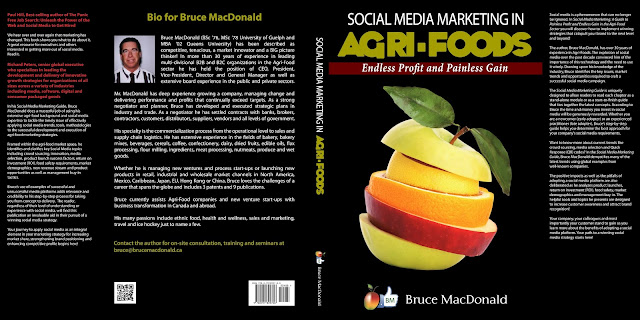

Check out my new e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain"

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Thanks for taking the time

No comments:

Post a Comment