The Greek-yogurt phenomenon in America left big food firms feeling sour. They are trying to get better at innovation

His new take on an age-old recipe, which comes with a variety of added fruits, has survived the perils of youth. Now it faces the problems of maturity. Established yogurt-makers, surprised by the Greek phenomenon, have woken up. Danone, the world’s biggest, launched its Oikos brand in 2010. Yoplait, owned by America’s General Mills, made a tragedy of its first Greek venture but has come back with a new concoction. Though still growing fast, Chobani has lost market share. It has begun what Mr Ulukaya terms its second chapter. In July it hired a chief operating officer; it is about to appoint a new advertising agency to promote the brand. Despite these corporate trappings, Chobani hopes to remain disruptive.FEW business careers have been as spectacular as Hamdi Ulukaya’s. He bought an 85-year-old yogurt factory in upstate New York in 2005 and sold his first pot of Chobani “Greek” yogurt 18 months later. This year he expects to sell more than $1 billion-worth of it. Greek-style yogurt’s share of America’s $6.1 billion market has risen from negligible when Chobani started to nearly half. “No category changed faster,” boasts Mr Ulukaya, the sole owner of the firm that makes Chobani.Some of the cleverest recent ideas in food have come from upstarts. Plum Organics helped pioneer baby-food pouches with spouts; a fifth of American baby food is now squirted rather than spoon-fed. Keurig, which makes single-serving coffee brewers, outsells all other coffee-makers in North America. Innocent, a British firm, gave smoothies a lift by showing them off in clear bottles. Big packaged-food companies are timid innovators, fiddling with flavour or cautiously extending their existing product lines, says Thilo Wrede of Jefferies, an investment bank. That is costing them customers, some of whom are defecting to fresher foods.

The son of a Kurdish farmer from Turkey, Mr Ulukaya doubted the conventional wisdom that Americans were hooked on sweet yogurt. The more delicately flavoured Greek sort—strained to remove the whey and thus packed with protein—was available at speciality stores in New York City but not widely beyond there. Mr Ulukaya thought it could have mass appeal. Supermarkets were receptive in the late 2000s, in part because they were looking for products to win back recession-weary shoppers. The extra protein appealed to the health-conscious among them.

It is easy to see why Big Yogurt did not spot this. Foodmakers had been wrong-footed by earlier health crazes, like the low-carb fad. Making Greek yogurt is complicated and expensive. It uses three times as much milk per cup of finished product than the conventional kind. Danone has had to speed up its milk deliveries and invest $100m a year, mainly to compete with Chobani. As in other industries, large firms face an “innovation paradox”, says Rob Wengel of Nielsen, a market-research company. The skills required to run the existing business well can clash with the “creativity and focus” needed for invention.

Giants often deal with the pesky innovators by buying them. Campbell, famous mainly for tinned soup, bought Plum this year; Coca-Cola acquired Innocent. But they may be getting better at coming up with their own ideas. Of 14,000 consumer-goods launches between 2008 and 2011, 48 were “breakthrough products”, meaning that they were distinctive, had sales of at least $50m in their first year and held on to at least 90% of that in their second. Most came from big firms, according to Nielsen (though the criteria are loose enough to include Oikos, the Chobani copycat).

Companies have been cutting the number of new-product launches by 7-10% a year to focus on potential blockbusters. They have become better at understanding “how consumers live their lives”, which improves the odds of success, says Mr Wengel. Chobani, which does its own fly-on-the-wall consumer research, considers that to be one of its strong points.

As rivals erode that advantage, Chobani is betting that surprises will keep coming from its distinctive culture. This fuses the small-town values of upstate South Edmeston, the site of Chobani’s first plant, with the Silicon Valley vibe of its SoHo offices. Unlike other gastro-entrepreneurs, Mr Ulukaya says he has no intention of selling up. The planned investment in Chobani’s brand should help the company launch new products, and not just yogurts. “The whole supermarket is our playground,” says Mr Ulukaya. Bigger firms must wonder what’s coming next.

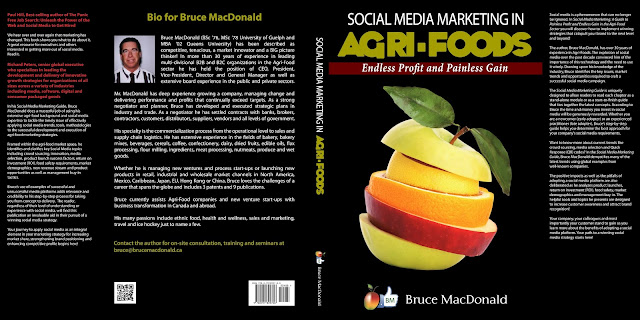

Check out my latest e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain"

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Thanks for taking the time!

No comments:

Post a Comment