DROUGHT-PROTECTING CHEMICAL DISCOVERED TO PREVENT CROP LOSS

Posted in News, Science & Research, Crop, Agriculture, Demographic, Nutrition, Economics, Water,Market Trends, Costs, Fruits / Vegetables, Grains / Pasta / Tuber, Bakery / Cereal

RIVERSIDE, Calif.—A new drought-protecting chemical has been discovered at the University of California, Riverside (UCR) that has potential for becoming a powerful tool for crop protection, according to new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Plants require water to thrive and with record breaking temperatures that have been hitting the country in the last two years global food prices reached a record high in December 2010.

Land plants have intricate water sensing and drought response systems that are tuned to maximize their fitness in the environment they live in. Plants grown in low-water environments grow slowly in order to save water that is available to them.

"But since farmers have always desired fast-growing varieties, their most valued strains did not always originate from drought-tolerant progenitors," Sean Cutler, an associate professor of plant cell biology and research team leader said. "As a result, we have crops today that perform very well in years of plentiful water but poorly in years with little water. This dilemma has spawned an active hunt for both new drought-tolerant crops and chemicals that farmers might use for improving crop yield under adverse conditions."

During their research, Cutler and his team used Arabidopsis—a model plant—and focused their efforts on tinkering with one of the plant endogenous systems involved in drought responses. Stomatas, tiny pores in leaves, which dynamically open and close to control the amount of water lost to the environment by evaporation close firmly to limit water loss during drought. A small hormone called abscisic acid (ABA) orchestrates the opening and closing of the pores. Cells throughout the plant produce increasing amounts of ABA as water levels decrease. ABA then moves throughout the plant to signal the stressful conditions and close the stomata. Inside plant cells, ABA does its job by turning on a special class of proteins called receptors.

"If you can control the receptors the way ABA does, then you have a way to control water loss and drought-tolerance," Cutler said. "It has been known for many years that simply spraying ABA on plants improves their water use and stress tolerance, but ABA itself is much too expensive for practical use in the field by farmers."

The chemical quinabactin was discovered and named by Cutler and his team. It is an inexpensive synthetic chemical that mimics a naturally occurring stress hormone in plants and helps the plant cope with drought conditions. Quinabactin mimics ABA but is simpler to make.

By studying how the new molecule activates the ABA receptors that are involved in drought tolerance, the team also learned more about the underlying control logic of the stress response system and provided new information that can be used for others interested in developing similar molecules,

"This is a competitive arena that includes agrichemical giants who are busily working to bring similar drought-protecting molecules to market, so this is a landmark discovery because quinabactin is the first-in-class synthetic molecule of its kind," Cutler said.

UCR Office of Technology Commercialization (OTC) is working with an agricultural leader, Syngenta Biotechnology, Inc., to develop the technology and bring it to the market.

Land plants have intricate water sensing and drought response systems that are tuned to maximize their fitness in the environment they live in. Plants grown in low-water environments grow slowly in order to save water that is available to them.

"But since farmers have always desired fast-growing varieties, their most valued strains did not always originate from drought-tolerant progenitors," Sean Cutler, an associate professor of plant cell biology and research team leader said. "As a result, we have crops today that perform very well in years of plentiful water but poorly in years with little water. This dilemma has spawned an active hunt for both new drought-tolerant crops and chemicals that farmers might use for improving crop yield under adverse conditions."

During their research, Cutler and his team used Arabidopsis—a model plant—and focused their efforts on tinkering with one of the plant endogenous systems involved in drought responses. Stomatas, tiny pores in leaves, which dynamically open and close to control the amount of water lost to the environment by evaporation close firmly to limit water loss during drought. A small hormone called abscisic acid (ABA) orchestrates the opening and closing of the pores. Cells throughout the plant produce increasing amounts of ABA as water levels decrease. ABA then moves throughout the plant to signal the stressful conditions and close the stomata. Inside plant cells, ABA does its job by turning on a special class of proteins called receptors.

"If you can control the receptors the way ABA does, then you have a way to control water loss and drought-tolerance," Cutler said. "It has been known for many years that simply spraying ABA on plants improves their water use and stress tolerance, but ABA itself is much too expensive for practical use in the field by farmers."

The chemical quinabactin was discovered and named by Cutler and his team. It is an inexpensive synthetic chemical that mimics a naturally occurring stress hormone in plants and helps the plant cope with drought conditions. Quinabactin mimics ABA but is simpler to make.

By studying how the new molecule activates the ABA receptors that are involved in drought tolerance, the team also learned more about the underlying control logic of the stress response system and provided new information that can be used for others interested in developing similar molecules,

"This is a competitive arena that includes agrichemical giants who are busily working to bring similar drought-protecting molecules to market, so this is a landmark discovery because quinabactin is the first-in-class synthetic molecule of its kind," Cutler said.

UCR Office of Technology Commercialization (OTC) is working with an agricultural leader, Syngenta Biotechnology, Inc., to develop the technology and bring it to the market.

Sources:

- University of California, Riverside: Improving Crop Yields in a World of Extreme Weather Events

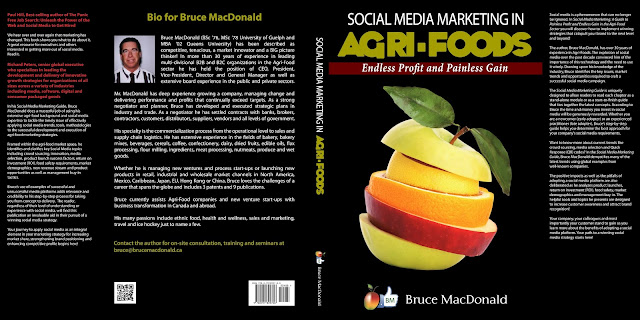

Check out my latest e-book entitled: "Social Media Marketing in Agri-Foods: Endless Profit and Painless Gain"

The book is available on Amazon and Kindle for $4.99 USD. Visit amazon/Kindle to order now:

http://www.amazon.ca/Social-Media-Marketing-Agri-Foods-ebook/dp/B00C42OB3E/ref=sr_1_1?s=digital-text&ie=UTF8&qid=1364756966&sr=1-1

Thanks for taking the time!

No comments:

Post a Comment